题目解析:

【题目翻译】下列哪一项最能说明第5段与第4段的关系?

A:这两段都比较了撒哈拉以南地区谷物农业和畜牧业作为粮食生产战略的有效性。

B:第5段质疑第4段关于撒哈拉以南地区农业转移的相对重要性的观点。

C:这两段都强调了撒哈拉以南的农业实践需要很长时间才能发展的观点。

D:第5段提供了关于第4段提出的将农业转移到撒哈拉以南的做法的进一步细节。

【判定题型】:根据题目问法,题目询问xxx组成或构成方式/段落与段落的关系/某一段在全文中所起的作用,故判断本题为组织结构题。

【内容分析】题目问,第四段和第五段的关系是什么?我们先分别来看第四段和第五段的内容。第四段主要讲了牧民们采用轮耕法,即“刀耕火种”发,用最少的设备和精力来耕种。而第五段进一步分析了“刀耕火种”法的优点以及传播。

【选项分析】

A选项:两段都在比较撒哈拉以南地区谷物农业和畜牧养殖作为食物生产方式的有效性。错误,因为四、五两段主要是在将谷物种植,且没有将种植农作物与畜牧业进行对比,故A选项排除。

B选项:第五段质疑了第四段所持的关于撒哈拉以南地区轮耕法的相对重要性的观点。错误,因为第五段没有任何反驳第四段观点的迹象,故B选项排除。

C选项:两段都在强调撒哈拉以南地区的农业生产是经过很长时间才发展起来的。错误,因为第四段和第五段都没有强调农业生产花很长时间发展,只有第五段的最后一句说专家预计轮耕法在2个世纪的时间里就覆盖了东非和西非2000平方公里的土地。但是这是在说明轮耕法发展的迅速,并不是强调它的发展要花很长时间。故C选项排除。

D选项:第四段中提到撒哈拉以南地区实行农耕法,第五段对此提供了更多的细节说明。正确,符合原文的篇章逻辑。故D选项正确。

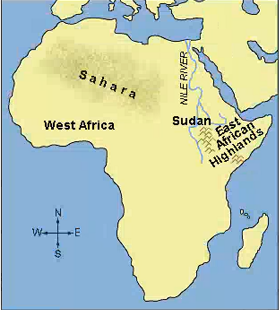

At the end of the Pleistocene (around 10,000 B.C.), the technologies of food production may have already been employed on the fringes of the rain forests of western and central Africa, where the common use of such root plants as the African yam led people to recognize the advantages of growing their own food. The yam can easily be resprouted if the top is replanted. This primitive form of "vegeculture" (cultivation of root and tree crops) may have been the economic tradition onto which the cultivation of summer rainfall cereal crops was grafted as it came into use south of the grassland areas on the Sahara's southern borders.

At the end of the Pleistocene (around 10,000 B.C.), the technologies of food production may have already been employed on the fringes of the rain forests of western and central Africa, where the common use of such root plants as the African yam led people to recognize the advantages of growing their own food. The yam can easily be resprouted if the top is replanted. This primitive form of "vegeculture" (cultivation of root and tree crops) may have been the economic tradition onto which the cultivation of summer rainfall cereal crops was grafted as it came into use south of the grassland areas on the Sahara's southern borders.